OUR PASSIONS

AND

INTERESTS

PLEASE SEND US AN EXAMPLE OF YOUR SPECIAL TALENTS SO WE CAN DISPLAY THEM FOR OTHERS TO ENJOY

FROM CRAIG HOUSEHAM:

Book overview

As possibly the longest serving Provincial Head of Department in South Africa, Dr Craig Househam shares his autobiographical journey: From a youth growing up in the apartheid era, to a doctor and then paediatrician, and the extraordinary career in public service that followed. From the advent of democracy to the AIDS crisis, Dr Househam was at the coalface of South African healthcare. Journey with him as he regales the reader with analysis, anecdotes and insights into the people and decisions that have influenced healthcare in South Africa over the past 25 years.

Craig Househam grew up in South Africa during the apartheid era, training as a doctor and then a specialist paediatrician followed by an extraordinary career in public service over four decades. From the advent of democracy to the AIDS crisis, Dr Househam was at the coalface of South African healthcare as a clinician, academic and senior bureaucrat during this period. He was actively involved in the tumultuous happenings that followed the democratic transition in South Africa in 1994.

He retired from the South African public service in 2015 and subsequently has pursued a career as an independent medical management consultant, author and health blogger. He has been engaged on numerous occasions to assist government with health related challenges serving on the boards of health related public entities and ministerial task teams. He remains a respected expert on healthcare matters in South Africa often engaged to speak on health related matters to a wide range of audiences.

As possibly the longest serving Provincial Head of Department in South Africa, Dr Craig Househam shares his autobiographical journey: From a youth growing up in the apartheid era, to a doctor and then paediatrician, and the extraordinary career in public service that followed. From the advent of democracy to the AIDS crisis, Dr Househam was at the coalface of South African healthcare. Journey with him as he regales the reader with analysis, anecdotes and insights into the people and decisions that have influenced healthcare in South Africa over the past 25 years.

Craig Househam grew up in South Africa during the apartheid era, training as a doctor and then a specialist paediatrician followed by an extraordinary career in public service over four decades. From the advent of democracy to the AIDS crisis, Dr Househam was at the coalface of South African healthcare as a clinician, academic and senior bureaucrat during this period. He was actively involved in the tumultuous happenings that followed the democratic transition in South Africa in 1994.

He retired from the South African public service in 2015 and subsequently has pursued a career as an independent medical management consultant, author and health blogger. He has been engaged on numerous occasions to assist government with health related challenges serving on the boards of health related public entities and ministerial task teams. He remains a respected expert on healthcare matters in South Africa often engaged to speak on health related matters to a wide range of audiences.

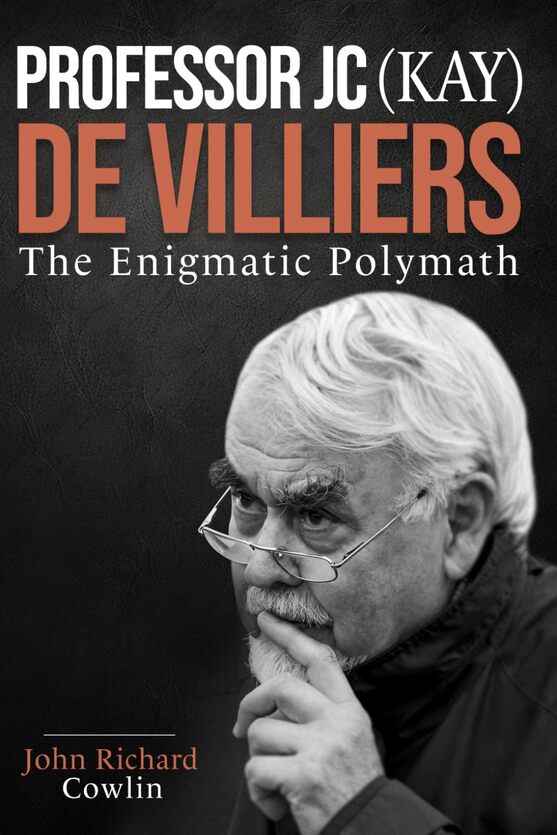

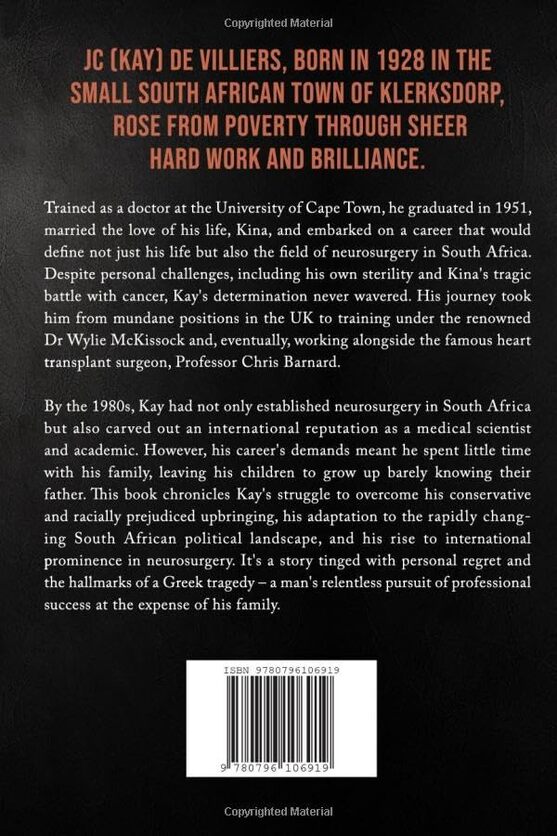

FROM JOHN COWLIN:

From Small-Town Beginnings to Global Neurosurgery Luminary: The Remarkable Journey of a South African Doctor

JC (Kay) De Villiers, born in 1928 in the small South African town of Klerksdorp, rose from poverty through sheer hard work and brilliance. Trained as a doctor at the University of Cape Town, he graduated in 1951, married the love of his life, Kina, and embarked on a career that would define not just his life but also the field of neurosurgery in South Africa. Despite personal challenges, including his own sterility and Kina's tragic battle with cancer, Kay's determination never wavered. His journey took him from mundane positions in the UK to training under the renowned Dr Wylie McKissock and, eventually, working alongside the famous heart transplant surgeon, Professor Chris Barnard.

By the 1980s, Kay had not only established neurosurgery in South Africa but also carved out an international reputation as a medical scientist and academic. However, his career's demands meant he spent little time with his family, leaving his children to grow up barely knowing their father. This book chronicles Kay's struggle to overcome his conservative and racially prejudiced upbringing, his adaptation to the rapidly changing South African political landscape, and his rise to international prominence in neurosurgery. It's a story tinged with personal regret and the hallmarks of a Greek tragedy – a man's relentless pursuit of professional success at the expense of his family.

Reader Reviews

“This is a scintillating read based on comprehensive research. It bristles with insights on an extraordinary man and his times.”

~ Albert Grundlingh - Emeritus Professor of History Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

“It is a great tour de force about a marvelous person, quite superb.”

~ Professor Edward R Laws, Professor of Neurosurgery, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

“Dr John Cowlin has written what is likely to be the definitive history of this important but enigmatic figure in South African medicine. He takes us from his rural roots through medical and surgical training to professor with outstanding insights. De Villiers was not just a doctor but had a personal life that defined his work, and the author provides an unstinting but fair evaluation of his personality. John is to be congratulated on an excellent contribution to the history of neurosurgery. This book should be in all medical libraries.”

~ Associate Professor Robert M Kaplan, Western Sydney & Wollongong University - forensic psychiatrist, historian and biographer.

JC (Kay) De Villiers, born in 1928 in the small South African town of Klerksdorp, rose from poverty through sheer hard work and brilliance. Trained as a doctor at the University of Cape Town, he graduated in 1951, married the love of his life, Kina, and embarked on a career that would define not just his life but also the field of neurosurgery in South Africa. Despite personal challenges, including his own sterility and Kina's tragic battle with cancer, Kay's determination never wavered. His journey took him from mundane positions in the UK to training under the renowned Dr Wylie McKissock and, eventually, working alongside the famous heart transplant surgeon, Professor Chris Barnard.

By the 1980s, Kay had not only established neurosurgery in South Africa but also carved out an international reputation as a medical scientist and academic. However, his career's demands meant he spent little time with his family, leaving his children to grow up barely knowing their father. This book chronicles Kay's struggle to overcome his conservative and racially prejudiced upbringing, his adaptation to the rapidly changing South African political landscape, and his rise to international prominence in neurosurgery. It's a story tinged with personal regret and the hallmarks of a Greek tragedy – a man's relentless pursuit of professional success at the expense of his family.

Reader Reviews

“This is a scintillating read based on comprehensive research. It bristles with insights on an extraordinary man and his times.”

~ Albert Grundlingh - Emeritus Professor of History Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

“It is a great tour de force about a marvelous person, quite superb.”

~ Professor Edward R Laws, Professor of Neurosurgery, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA.

“Dr John Cowlin has written what is likely to be the definitive history of this important but enigmatic figure in South African medicine. He takes us from his rural roots through medical and surgical training to professor with outstanding insights. De Villiers was not just a doctor but had a personal life that defined his work, and the author provides an unstinting but fair evaluation of his personality. John is to be congratulated on an excellent contribution to the history of neurosurgery. This book should be in all medical libraries.”

~ Associate Professor Robert M Kaplan, Western Sydney & Wollongong University - forensic psychiatrist, historian and biographer.

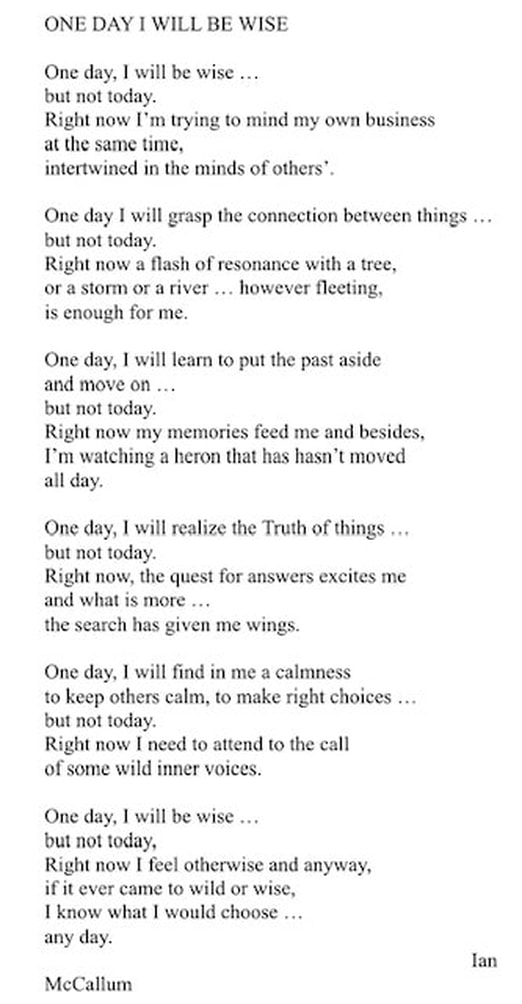

FROM IAN McCALLUM:

| an_unfamiliar_silence.doc | |

| File Size: | 82 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

MUSINGS OF ROB DYER:

On the outside

In the mid 1990s I was asked to provide testimony to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings on my supposed area of expertise - the health problems experienced by detainees - most specifically in Durban and the broader KZN area. I refused to testify. In truth, it would be more accurate to say, I ran away. I was simply unable to bring myself to revisit the horror to which I had borne witness.

I could not, at that stage, bring myself to revisit the nightmare of attempting to care for detainees that we had experienced in the 1980s. The sense of relief I had felt to be finally released from the demands, the sleepless nights, the fears, nay, the terrors, simply overwhelmed me. The constant vigilance had finally got to me.

My decision has haunted me ever since. My soul aches with guilt that, in the moment of triumph, I was unable to bring myself to participate. In truth, my own soul, my own psyche, had fragmented and I submerged myself in work. Fortunately, as a doctor, there is ample room to hide behind a caring facade.

A perceptive psychologist friend and colleague of mine remarked that, perhaps, I myself needed help. Perhaps I had also fallen apart, like so many of those I had counselled and treated over the years. Certainly my behaviour at that time would, to an extent, support such a contention. I destroyed all the records I had which related to NAMDA, to DESCOM and to the Detainees Health Group. I discarded that part of my life as if it never existed. Fortunately, for the preservation of my soul, I had a caring profession on which to fall back. The practice of medicine is all consuming, if you allow it to be. Just as the struggle for freedom and justice had been.

Perhaps my testimony, my recollections, remain pertinent.

I was born in 1949, in Durban, a fractured town mingling colonial stuffiness with vibrant African colours and Indian mystique. The whites, at the time I was born, were largely English speaking and seemed to owe an allegiance to the British crown and the empire, rather than to South Africa. I distinctly remember, at the time of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953, me and my cousin, Geoff, being given little Union Jacks by my (paternal) grandmother and the two of us marching up and down waving them triumphantly. Later, we were taken to the cinema, never the “movies” (too American) or the “films” (too vulgar), to watch a newscast, in black and white, of the event. If memory serves me correctly, the audience stood and sang “God save the Queen”. The bizarre nature of this only struck me much later in my life. What it did highlight, however, was just how contradictory our position in Southern Africa was. The question of whether we belong in Africa is then, perhaps, pertinent to ask.

South Africa is, predominantly, a black country. Arguments which abound about who (i.e. which “race”) arrived here first have little relevance. Currently, over 85% of the the population are Black South Africans, with Whites making up around half of the remaining 15%. Formal (legislated) apartheid began in 1948, with the advent to power of the Nationalist party government. Prior to this, however, social, legislative and economic factors had already conspired to deprive the black majority of any meaningful control over their lives. Apartheid merely entrenched and strengthened the available repressive machinery.

The seeds for this had been sown as early as 1652 with the arrival of the first settlers, of Dutch origin, at the Cape. Over the ensuing 200 or so years, via a process of military and economic domination, often aided and abetted by the Christian church, the Black population was systematically subjugated. The 1913 Land Act, promulgated 35 years before formal apartheid was enacted, gave concrete substance to this, bringing 87% of South Africa’s land under the control of the white government of the day and confining Black South Africans, the vast majority, to the rest. Unless we understand that, we understand nothing. Talk of “forgive and forget” becomes, to me, meaningless against that backdrop.

Finding my way

1972

Oh to be young and White

Cape Town in winter can be awful. The rain never ends and the cold chills the bone.But the long summer evenings are like paradise- at least when the wind doesn’t blow.

It is a city of paradox. The least African of all South Africa’s great cities. A maverick anachronism at the extreme tip of this great, dark, violent and exquisitely beautiful continent. It is, simultaneously, the most European of all African cities and the site of the oldest established Black African township in South Africa. Langa township, the original apartheid ghetto, founded decades before formal apartheid even existed. Later, in the budding bloom of my more advanced political consciousness, I was to spend an extraordinarily happy and productive year working in Langa Day Hospital, but more of that later.

None of this mattered on a night, one of many in 1972, where we spun recklessly across the freezing rain spattered tarmac. Two am Saturday night, Sunday morning, pissed as newts skidding around the wet, empty parade parking lot. The parade, ah the parade, the Grand Parade. Busy parking lot by day, home to the hawkers and flower sellers, the pickpockets and street comedians and by night an empty wasteland and home to the two finest late night eateries in the town- Mick’s Pie Cart and Claude’s kiosk.

Flip the coin, you decide “Mick’s” or “Claude’s”. Heads “It’s Mick’s”, skid up to the kiosk, jump out order hamburgers and chips, hangover food. “Hey buggers, it’s tails- it’s Claude’s” - “Wait for me, you bastards” and zoom back off to the other side of the parade. Oh we were great. United in our drunken, self confident student brashness. Young White kids with scarcely a care in the world. Secure in our wonderful, protected, unquestioning world. Filled only with certain certainties and booze filled profundity. How little did we know.

1973

The “political” events of 1973, most notably the Durban strikes, caused me, probably for the first time in my life, to begin to reflect on the world around me, its manifest injustices and my place and role within that world. Perhaps it was that these seismic events were taking place in Durban, my home town, that brought them into sharp relief. In any event, once your eyes have been opened to injustice you can no longer close those eyes- no longer avert your gaze. That awareness, that quest for what I will term “ social justice” has consumed me ever since.

Some years later, I was at a protest meeting held at UKZN addressed by my friend Halton Cheadle, who had been served with a banning order in 1973 for his part in the Wages Commission. Halton, in his laconic humorous style, recounted the first day of the strike when workers at the Pinetown textile factories, most notably Frame, poured out of their workplaces and into the streets. One of the marchers grabbed a red roadside warning flag to wave in celebration, the kind of flag we see at every construction site anywhere. It didn’t take the eagle eyed, ultra suspicious and conspiracy obsessed security police long to draw attention to the significance of the RED FLAG and thus who was clearly behind the strikes!

Musings

I can’t get these images out of my mind:

1976

The cathedral at Chartres is an exquisite building. The shiny gold, glinting stained glass windows throw sunlit dimples onto the warm, worn flagstone floor. If, on a fine day, you look up you can truly imagine you have entered the kingdom of heaven.

I joined the English guide tour on that day long ago, went back that afternoon and then morning and midday for the next three days. It seemed a strange thing for a comfortably agnostic and intellectually atheist young South African to do. From that moment on, however, the Gothic cathedrals of Europe have enthralled me in a way no other buildings have. So much so, that, whenever I am in a European city, the one building I ensure I visit is the local Gothic cathedral. Perhaps it is the knowledge that these extraordinary buildings were built in an era when it was possible for all the great artists and craftsmen of Europe to come together and share in the construction of each cathedral, sometimes decades in the making. To share their skills and to focus all their endeavours on a common goal- the construction of a masterpiece.

Would that humans could find it in themselves to be so focussed and supportive of each other at other times.

Who knows what inner cravings drive us so?

Launch of the UDF 20 August 1983

A cold and blustery day - overcast and squally. A veritable hubbub of people. Buzzing. Heady mingling. Intoxicating.

And a diminutive Terror Lekota, far away on the stage and the singing joyful crowd at once loud and boisterous but respectful, expectant, anticipatory, in their quietness.

Frank Chikane appeared on stage to outline the day. Articulate, focused - and then he stopped, paused mid sentence - and time stood still for one incredible moment as Helen Joseph limped across the stage on her elbow crutch. Slow, halting and then she stopped at her seat - and turned - fist upraised in the classical salute - before sitting down. And the crowd erupted.

How could we not belong? Step out of yourselves and Africa’s warm heart is yours for the taking.

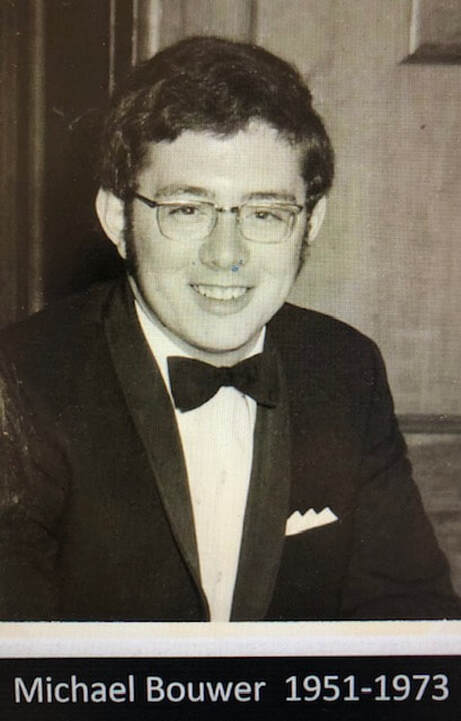

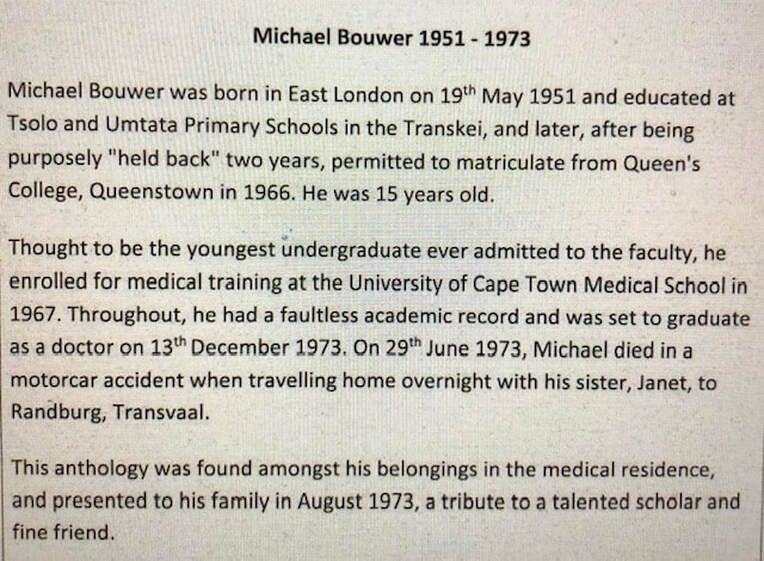

| michael-bouwer-1951-1973-an-anthology__1_.pdf | |

| File Size: | 6687 kb |

| File Type: | |