RECONCILIATION

A time to mend fences, before it is too late

The below is part of a thought provoking speech delivered by a rabbi on The Day Of Atonement.

Against whom should we hold grudges? Certainly not those around us - our family, friends and co-workers. Life is too short - after all, we only have one soul.

And yet, so many of us do hold grudges. We have a difficult time forgiving. We see it all the time: in our offices, at weddings, at funerals.......

Fathers who cannot talk to their sons. Brothers and sisters who hang on to childhood arguments. Aunts, uncles and cousins deprived of loving or even knowing each other because of some ancient family feud.

Children are deprived of grandparents. Lovers deprived of each other's love. Families filled with anger, silence, smugness, nervousness - all of it because we are unable to forgive.

There are many who feel that they cannot forgive - the pain of the past is replayed over and over - they are deeply scarred - they move in a world of memory. For these people - forgiveness is a distant concept. And yet, healing comes when forgiveness is not seen as an impossibility - but a goal to be reached - for only when there is forgiveness can there be true healing. No one can forget the pains of the past - but we can forgive.

But of course, I'm only talking about the dysfunctional families...right? People with real problems: Abusers, chemically dependent, mentally ill -- we're all better than that, aren't we?

Maybe. But who among us has not slammed a door in anger this past year? Who hasn't hurled a cutting remark or two just to inflict a little pain on a loved one? Who has been given an opportunity to heal - to comfort, to give love - and rejected it?

A while ago, the writer came across and old Ann Landers column.

In it was a letter that read:

Dear Ann Landers,

I have suddenly become aware that the years are flying by. Time somehow seems more precious. My parents suddenly seem old. My aunts and uncles are sick, and I fear they don't have many years left. I haven't seen some of my cousins for several years. I really love my family, Ann, but we have grown apart.

I am also thinking of my friends, some I've known since childhood. Those friendships have become more precious as the years pass. Nothing warms the heart like sharing a laugh with someone you've known for years.

Then my thoughts turn to the dark side. I remember the feelings I've hurt and I recall my own hurt feelings, the misunderstandings and the unmended fences.

I have a close friend in New York I haven't spoken to in three years. Another 28-year relationship in Seattle is on the rocks. We're both 41 now, and time is marching on.

I think of my mother and her sister, who haven't spoken to each other in 5 years. As a result of that argument, my cousin and I haven't spoken either. I don't know if she has children. Neither of us has met the other's husband. What a waste of precious time! I'm sure there are millions of people in your reading audience who could tell similar stories.

Wouldn't it be terrific if a special day could be set aside to reach out and make amends? We could call it "Reconciliation Day." Everyone would vow to write a letter or make a phone call and mend a broken relationship. It would also be the day on which we would all agree to accept the olive branch extended by a friend. this day could be the starting place. We could go from there to heal the wounds in our hearts and rejoice in a new beginning.

Signed,

Van Nuys.

Ann Landers suggested April 2 be designated as National Reconciliation Day.

Another story:

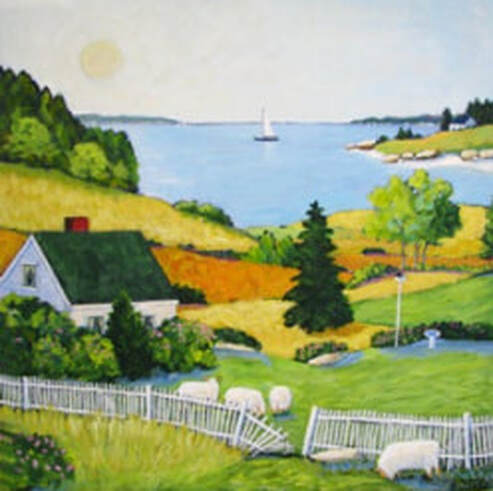

I was interrupted by a hammering sound coming from the house next door.

I stood up, walked over to the window and noticed my next-door neighbor replacing a small section of his white picketed fence. The fence had been damaged the previous week. As I stood there watching him take down the damaged section and replace it with a new fence; I wished the problems in life could be fixed so easily.

My mind drifted back to the relationship I had with (you fill in the blank), or you could say the relationship I did not have with (xxxxx). I continued to watch my neighbor as he methodically replaced the damaged section of fence.

The first thing he did was to recognize that the fence had a problem; it was damaged. Then he had to remove the damaged portion of the fence. Next, he nailed the new fence into place, and the last thing he did was paint the fence. After he had finished the process, you could not tell that the fence had been damaged. It looked brand new.

I turned away from the window, and sat back down on the couch. It suddenly occurred to me that I had a damaged fence in my own life, and it was up to me to repair it.

A time to mend fences...life's too short

Delicate Art of Fixing a Broken Friendship

Forgiving Is Good for You, Researchers Say, But Take It Slow; You May Be Ready to Start Over, But Your Friend May Not

By Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : July 26, 2011

A friend emailed me one evening to say she felt I wasn't there when she needed me.

I was stunned. I reminded her that I'd already spoken with her twice that day about a problem she had. She replied with a list of all the things she ever did for me. We bickered, via email, for the better part of an hour. Then angry and hurt, I typed these words and hit send: "This friendship isn't working for me anymore. I am bowing out."

Whoa... How was I going to fix that?

Some friendships are meant to end. Pals move away, grow apart, or something happens to make it clear that the relationship isn't mutually beneficial anymore. The memories are good, but it's time to move on.

Last year, I wrote about how to terminate a friendship efficiently and kindly, minimizing collateral damage with mutual friends and leaving the door open for possible future reconciliation ("How to Break Up with a Friend").

Because here's the thing with friendship breakups: Sometimes you come to regret them.

Make-Up Kit

Here are some tips for mending a broken friendship.

- When in doubt, err on the side of trying to reconcile.

- Vent to a third party who is supportive of the friendship, not to your estranged friend.

- You may be ready to make up, but don't assume your friend is, too. Invite your friend to work with you.

- Ask what you did wrong—and listen to the answer. Apologize. Take it slow. Rebuilding trust takes time.

A good friend is an emotional safe haven, providing support, guidance and laughter. When someone like that is suddenly gone from your life, it can be heart-wrenching. But how do you go about rebuilding a friendship that has splintered? When do you reach out? What do you say, and what if your former friend doesn't want to hear it? Texting "I'm sorry" probably won't cut it.

It bears saying that it's best not to let conflict become a crisis in the first place. "A relationship is an active process, and a repair should be an ongoing process, as well," says Frederic Luskin, a psychologist, director of the Forgiveness Project at Stanford University, which researches how forgiveness is good for mental and physical health, and author of "Forgive for Good." "You need to pay attention and not just be wrapped up in what you need to say," he says. If you have an argument, address the situation right away. Acknowledge your friend's feelings. Ask him to tell you how he feels. Apologize.

If you do end up estranged from your friend, find a way to make peace—even if you feel you weren't at fault or the forgiving isn't mutual. Forgiveness—asking for it and granting it—is good for your health. Research shows it lowers your blood pressure, decreases depression and has a positive effect on the nervous system, says Dr. Luskin.

Is there a time limit on mending a broken friendship? It depends, the experts say. Time can make the situation worse, allowing people to stew in their grievances too long, or letting them forget what was good about the union in the first place. But often time heals—especially if the parties mellow, mature or otherwise change their perspectives.

"What is important is what happens during the time of noncommunication," says Daniel L. Shapiro, a psychologist, director of the Harvard International Negotiation Program and co-author of "Beyond Reason: Using Emotions as You Negotiate." "Am I trying to better understand myself and my estranged friend's perspective?" he asks. "Or am I demonizing the other?"

Dr. Shapiro works with negotiators who are political adversaries or from estranged countries, to help them cope with the emotional dimension of conflict and negotiation and to deal more effectively with their differences. He teaches each side to dig beneath complicated emotions that may bog down the reconciliation process, and focus on five core concerns to foster positive feelings: Appreciation—meaning each party needs to feel heard and valued. Autonomy—each side needs freedom to decide if and when he or she wants to make up. Affiliation—each side needs to close the distance to regain closeness. Status—each needs to recognize that they contributed to the conflict. Role—each needs to adopt the position of listener, problem solver or healer.

Each side needs to be patient. Friends trying to reconcile shouldn't expect an immediate return to closeness, Dr. Shapiro says. They need to regain trust.

At first, I was reluctant to make up with my friend. I was hurt that she'd lashed into me. She responded to my silence over the next few days by periodically emailing me goofy photos of cute animals, which only irritated me more. I told her I needed space; she told me to take as long as I needed, that she would be patient.

Then my mom piped up. She knew how much this friendship meant to me. After hearing my side of the argument, she told me to stop being so stubborn and apologize. So I wrote my pal and said, "I miss you and I'm sorry I'm such an idiot." She excitedly responded that she was sorry too and happy to move on. (It pains me to admit that no matter how old I get, mom often still knows best.)

A few years ago, Wendy Knight, 46, a publicist in Panton, Vt., accused a very good friend of hers of hitting on her boyfriend. The friend was speechless and said she would never do that. The next day, the woman told Ms. Knight in an email that there was no point in being friends if she really felt that way. "I was actually surprised," Ms. Knight recalls. "I thought, 'Wait a minute, I didn't think this is how she would respond.' How silly of me."

Over the next year, Ms. Knight realized she was devastated over the loss of her friend. The two had often hiked and shared meals together. They had supported each other through relationship breakups and the loss of two parents. Now that Ms. Knight had broken up with her boyfriend, she missed her girlfriend.

So Ms. Knight composed a handwritten letter of apology to her friend saying she regretted causing her so much pain. She explained that she had taken the insecurity she felt in her relationship with her boyfriend out on her friend, and asked for her forgiveness. She told her friend how much she missed her.

The friend called immediately. She said that she cried when she read the letter. The two women chatted and slowly began renewing a friendship, emailing and talking on the phone regularly. Ms. Knight went to visit her friend in Texas, where she'd moved. Then they started going on vacations together. Today they are closer than ever.

Sibling Rivalry Grows Up

Adult Brothers and Sisters Are Masters at Digs; Finding a Way to a Truce

By Elizabeth Bernstein : WSJ : March 20, 2012

Marianne Walsh and her sister, Megan Putman, keep track of whose kids their mother babysits more. They also compete with each other over parenting styles (Ms. Walsh is strict, Ms. Putman is laid back) and their weight.

"My kids play more instruments, so I am winning in piano," says Ms. Walsh, 38, the younger of the two by 13 months. "But she won the skinny Olympics."

Adult sibling rivalry. Experts say it remains one of the most harmful and least addressed issues in a family. We know it when we see it. Often, we deeply regret it. But we have no idea what to do about it.

Ms. Walsh and Ms. Putman have been competitive since childhood—about clothes, about boyfriends, about grades. Ms. Walsh remembers how in grammar school her sister wrote an essay about their grandfather and won a writing award. She recited it at a school assembly with her grandpa standing nearby, beaming. Ms. Walsh, seething, vowed to win the award the next year and did.

Ms. Putman married first. Ms. Walsh, single at the time, clearly recalls the phone call when her sister told her she was pregnant. "I was excited because this was the first grandchild. Then I got off the phone and cried for two hours," says Ms. Walsh.

Ms. Putman, 39 and a stay-at-home-mom in Bolingbrook, Ill., remembers that she too felt jealous—of her sister's frequent travel and promotions in her marketing career. "The way my parents would go on and on about her really made me feel 'less than,' " Ms. Putman says.

Ms. Walsh eventually married, had a son and named him Jack. Seven weeks later, Ms. Putman gave birth to a son and named him Jack. The discussion? "That was always my boy name." "I never heard you say that."

Sibling rivalry is a normal aspect of childhood, experts say. Our siblings are our first rivals. They competed with us for the love and attention of the people we needed most, our parents, and it is understandable that we occasionally felt threatened. Much of what is written about sibling rivalry focuses on its effects during childhood.

But our sibling relationships are often the longest of our lives, lasting 80 years or more. Several research studies indicate that up to 45% of adults have a rivalrous or distant relationship with a sibling.

People questioned later in life often say their biggest regret is being estranged from a sister or brother.

The rivalry often persists into adulthood because in many families it goes unaddressed. "Most people who have been through years of therapy have worked out a lot of guilt with their parents. But when it comes to their siblings, they can't articulate what is wrong," says Jeanne Safer, a psychologist in Manhattan and author of "Cain's Legacy: Liberating Siblings from a Lifetime of Rage, Shame, Secrecy and Regret."

Dr. Safer believes sibling rivals speak in a kind of dialect (she calls it "sib speak"). It sounds like this: "You were always Mom's favorite." "Mom and Dad are always at your house but they never visit me." "You never call me."

"It's not the loving language that good friends have," Dr. Safer says. "It's the language of grievance collection."

It's hard to know what to say in response. "You are afraid that what you say will be catastrophic or will reveal awful truths," Dr. Safer says. "It's a lifelong walk on eggshells."

Sibling discord has been around since the Bible. Cain killed Abel. Leah stole Rachel's intended husband, Jacob. Joseph fought bitterly with his 10 older half brothers. Parents often have a hand in fostering it. They may choose favorites, love unevenly and compare one child with the other.

Dr. Safer draws a distinction between sibling rivalry and sibling strife. Rivalry encompasses a normal range of disagreements and competition between siblings. Sibling strife, which is less common, is rivalry gone ballistic—siblings who, because of personality clashes or hatred, can't enjoy each other's company.

Al Golden, 85, chokes up when he talks about his twin brother, Elliott, who died three years ago. The brothers shared a room growing up in Brooklyn, N.Y., graduated from the SUNY Maritime College in New York and married within a month of each other in 1947.

Yet Mr. Golden still remembers how their father often compared their grades, asking one or the other, "How come you got a B and your brother got an A?" He rarely missed a chance to point out that Elliott wasn't as good as Al in swimming.

When the boys were ready to get married, he suggested a double wedding. Mr. Golden put his foot down. "I shared every birthday and my bar mitzvah with my brother," he said. "I'll be damned if I am going to share my wedding with him."

Elliott Golden became a lawyer and eventually a state Supreme Court judge. Al Golden went into the mirror business, then sold life insurance. He says he always envied his brother's status and secretly took pleasure in knowing he was a better fisherman and owned a big boat. Once, Elliott asked him, "I am a lawyer. How come you make more money than me?" Mr. Golden says. "He meant: 'How come you are making more than me when you are not as successful?' But it made me feel good."

One day, Mr. Golden says, Elliott accused him of not doing enough to take care of their ailing mother. After the conversation, Mr. Golden didn't speak to his brother for more than a year. "It might have been the build-up of jealousies over the years," he says.

His brother repeatedly reached out to him, as did his nieces and nephews, but Mr. Golden ignored them.

Then one day Mr. Golden received an email from his brother telling a story about two men who had a stream dividing their properties. One man hired a carpenter to build a fence along the stream, but the carpenter built a bridge by mistake. Mr. Golden thought about the email then wrote back, "I'd like to walk over the bridge."

"I missed him," Mr. Golden says now. "I never had the chance to miss him before."

Dr. Safer says brothers' rivalries often are overt, typically focusing on things like Dad's love, athletic prowess, career success, money. Women are less comfortable with competition, she says, so sister rivalries tend to be passive-aggressive and less direct. Whom did Mom love best, who is a better mother now.

Brothers often repair their rivalries with actions. When women reconcile, it's often through talking. Ms. Putman and Ms. Walsh have learned to stop arguments using a trick from childhood. When a discussion gets heated, one sister will call out "star," a code word they devised as kids to mean the conversation is over. The sister who ends it gets the last word. "You may still be mad, but you adhere to the rules of childhood," Ms. Walsh says.

For some years, the two didn't socialize much. But when Ms. Putman's husband died last fall, Ms. Walsh, now a stay-at-home-mom in Chicago, helped plan the wake and write the obituary. Arriving at her sister's house one day before the funeral, Ms. Walsh found her in bed, crying, and climbed in next to her. The sisters said, "I love you," and Ms. Putman says she realized she was going to be OK.

"Lying there, I felt that if I've got my sister, I"ve got my strength," Ms. Putman says. "She is my backbone."

Putting a Stop to Sibling Rivalry

Fix the problem by addressing it head-on, says psychologist Jeanne Safer.

•The first step is to think. Who is this person outside his or her relationship with you? What do you like about your sibling? Remember the positive memories. Identify why you think the relationship is worth fixing—if it is.

•Take the initiative to change. It could be a gesture, like an offer to help with a sick child, a conversation or a letter. Be sincere and don't ignore the obvious. Say: 'These conversations between us are painful. I would like to see if we can make our relationship better.'

•Gestures count. Not everyone is comfortable talking about a strained relationship, especially men. But phone calls, invitations to spend time together, attempts to help should be seen as peace offerings.

•Consider your sibling's point of view. Try not to be defensive. What did childhood look like through his or her eyes? 'You have to be willing to see an unflattering portrait of yourself,' Dr. Safer says.

•Tell your sibling what you respect. 'I love your sense of humor.' 'I admire what a good parent you are.'

•And, finally: 'It won't kill you to apologize,' Dr. Safer says.

Why we have such different versions of history

Part of an article in NY Times : Sheila Heen : December 11, 2013

Before thinking about what to do, it’s useful to understand a few reasons why people on each side of a conflict can experience it so differently.

1. Emotional math.

Everyone gets frustrated, resentful, disappointed, or even enraged with others on occasion. It may come out as shouting, sarcasm, snippiness, or simply a put-upon silence. In those moments, we don’t see our emotional behavior as a big deal. They’re the ones who were being unusually annoying, it was a tense situation, you were tired. You know that your anger in that moment is not who you “really are.”

But to the other person, your anger is exactly who you are. Your emotional display is not incidental – it’s at the heart of the story they tell of what happened between you. From their point of view, your anger is the threat – the very thing they were coping with in that moment.

So you will tend to subtract your own emotions from the story, while the other person counts your emotions, say, double. And the same is true in reverse: You count their emotional reactions double, while they subtract them.

2. Emotions influence what sticks in memory.

Now factor in that memories that have emotions involved have a big red tag on them, so that we locate and recall those memories easily, even years later (and even when we would rather not recall them). This is why a sister remembers something that happened in childhood as a central moment in a conflict with her brother, while the brother literally has no memory of the event. If it had little emotional resonance for him at the time, he didn’t tag it. And so it didn’t “stick.”

Furthermore, there is evidence that each time we recall a memory, or retell it, we overwrite the memory itself. We think we still have the master file — that we remember exactly what happened accurately — but in fact we’re on version seven (or 77). And so is the other person. Over time each of our stories about what really happened grow farther and farther apart.

Simply recalling (your version of) an upsetting incident between you and a sibling — or experiencing the same kind of behavior from them now — can retrigger those feelings of hurt, confusion, disappointment, betrayal, or fear all over again. The original events were long ago — 10 or even 40 years past. But the feelings are happening (again) now.

Taken together, emotional math and emotional memories partly explain why our family stories of past and present can be so disturbingly different, or even why we have no idea what their grudge-holding story might be.

Here’s what not to do.

Don’t write them a long letter or email explaining your perspective. Even if you do a beautiful and skillful job of it, even if you apologize, it is unlikely to achieve your purposes. Why? Because inevitably some aspect of what you describe will feel “off” to them (“That’s not what happened!”) or will leave out parts that they feel are most important. And their interpretation of your motives for writing the letter is colored by emotion. Your desire to reconnect is seen as a desire to absolve yourself of guilt, to manipulate, or to appear to be righteously taking the high road.

So they finish reading your lovely letter and feel even more upset with you. Now they have even less incentive to reach out and talk because they’ve heard what you wanted to say (and it was wrong). Remember that email and letters aren’t dialogue. They’re monologue. And they’re the channel of communication that can escalate conflict most quickly.

If you need to send a note because you have no other way of contacting them, make it short and focused on the invitation and your feelings about what you miss in the relationship. Don’t explain your point of view. Don’t even apologize for specific things because they can argue with the specifics, or react to the fact that you’re not apologizing for other specific things. Just say something along these lines:

“Dear (Bob/Sally/Rufus),

I’ve really missed you. I know that the last few years have been hard, and I’m sure I’ve done things to exacerbate that. On my end, I feel hurt too. I would like to start the process of trying to heal our relationship, whatever that means for each of us. I miss my brother/sister, and I’d like to find a way to be closer ... “

If needed, this note can be given, in a sealed envelope, to a family member who can pass it along. The fact that you sealed it means the messenger isn’t in league with you on the message, and they don’t get put in the middle.

Now you have a few different directions you can go, depending on which strategy you want to try first. Some of the folks who wrote in have tried one or another of these, so they might choose to try a different one and see if you get a different reaction.

Three Reconnection Strategies:

Strategy 1: Don’t talk, just do.

Often family members cut off contact not because they like conflict, but because they hate conflict. Avoiding the stress seems most easily done by avoiding the people who produce the stress.

The problem is that this feeds on itself, making the conflict bigger, making it even more anxiety-producing. The last thing they want is to have to have a big conversation about it. That’s why they are avoiding you to begin with.

Sometimes, depending on the personalities involved, the best approach is to avoid the “big conversation” altogether, and just to start acting “normal” again. Melissa mentions that another sister was cut off for two years, which made me wonder, what eventually broke that dynamic? Send them a Christmas card. Send birthday gifts to their kids. Email them the recipe you found for those cookies grandma used to bake for you guys as kids. Small acts of kindness can start to get traction on re-establishing normalcy.

Strategy 2: Propose a conversation just about the future.

Sometimes it’s not worth sorting through the details of who did what and reacted to what. It may simply be that you want to propose talking about how to move on: “I’d love to get together, not to rehash what has happened, but to talk about how we’d each like things to be going forward. I miss you, and I’d love to find a way for our kids to spend more time together/for us to be supportive of mom together…..etc.”

Strategy 3: Initiate a conversation to understand the rift.

Let them know that you’d like to talk. Not so that you can talk them out of their feelings or their behavior, but so that you can better understand what’s happened between you. Melissa’s approach of telling her sister that she is welcome at their house anytime is helpful, but it leaves the ball in the sister’s court to take the initiative. She may be too stuck to be able to do that. Propose something more specific – let them know that you’d love to have coffee before the next family get together, at a specific time and at a favorite place perhaps. Or that you’ll be calling next week to check in on their reaction to your note. If you talk about it, do so one-on-one.

In that conversation, you’ll be doing two things – talking and listening. If you want them to listen to you, your best chance at making that happen is by first listening to them. Why? Because people simply do not take in what you have to say, cannot question or shift their perceptions, until they feel understood. To get meaningful communication moving, someone has to be the first to listen and that someone is going to have to be you.

Work hard to understand their perspective, and not to argue with it. Imagine that you’re a journalist who has to explain your sibling’s perspective to the public. Ask questions to clarify what they mean and how they felt. Assume that their story will have lots of partial truths (leaves out things, misinterprets things), be teeming with blame, and cast you as the bad guy. That’s O.K. They’ve come loaded for bear, and they expect a fight. Don’t give it to them. Don’t argue with their story; just work to understand it.

Don’t worry. You get to say your piece too. When you have spent enough time listening to and asking questions so that they feel heard and the energy behind it has settled down, you can turn to your perspective. The transition is important, because you’re not working to contradict, just to add your pieces of the puzzle to more fully understanding what went on between you:

"Thanks for telling me what’s been going on from your perspective. There are a number of things you said that I was unaware of, and there are things that are important to you that I just wasn’t thinking about. I’m starting to get a better sense of how upsetting it’s been for you…. [Agree with what you do agree with about what they’ve said. This helps them feel heard, and creates some common ground, whether it’s 5% or 65% of what they’ve said. After that, say….]

And, there are also some things that have happened between us that have also been upsetting to me…."

We call this using the “And Stance.” You can be upset, and I can be upset too. You can feel you are right, and I can be right about some things too. I contributed to the problem, and you contributed too. We need to talk about both.

When you describe your perspective, keep these ideas in mind.

Take responsibility for your contribution to the rift:

“Looking back, I can see why not inviting you to the wedding was hurtful. At the time I wasn’t sure what to do. I didn’t think you wanted to come, and I was also feeling so hurt myself that I wasn’t sure I was up to being upset on our wedding day….”

Don’t accuse them of bad intentions, just describe the impact:

“You may not have intended it, but when you took over the planning for mom’s birthday without consulting anyone, I was really hurt and confused……”

Say what you want for the future: Too often we get to the end of a big conversation and walk away unclear what happens next. This sets you both up for further disappointment if your expectations differ. Close by saying what you would like, or intend to do: “So I’d like to go back to getting together at the holidays….” Or “What if we have coffee every couple of weeks for awhile?” or even, “I want to think about some of what you’ve said, and I’ll call you next week….”

Whatever you try, remember that it takes time to normalize a relationship this estranged, and it’s also not a linear process. Things often get worse before they get better, and then go up and down even as they gradually, in the big picture, improve. So the dips and frustrations are normal, and not necessarily a signal that you should give up.

But the bottom line is that the only person you control in this relationship is yourself. Your goal should be to offer the most appealing and welcoming invitation to relationship that you can, consistently over time, and to feel proud of the way you handled it. How they choose to respond is up to them.

A special note to those who have curtailed family contact

If you are going to cut off ties or establish a boundary — and this can sometimes be a healthy reaction to unrelenting criticism or destructive hurt — here are two things to remember.

First, tell others why you are doing it. You think they already know; after all, your reasons are obvious or should be obvious to anyone who cares. But they really might not know. And if they don’t know, they are free to think the worst. When you inform them, don’t focus on others’ character (“I can’t be with the family because you are all so toxic and hateful.”) Instead, focus on how you’re feeling (“The last three times we’ve had big family get-togethers, my anxiety has just gone through the roof. I leave feeling judged and rejected. It’s too much for me to deal with, so I’m going to stay away this year.”). And if there are conditions under which you would increase contact, let them know (“If you can refrain from commenting on my weight or my spouse, we’ll come.”).

Second, remember that your kids are watching. They’re learning how to handle conflict in families and in relationships. There are no easy answers here, but at least be aware that what you do today may be what your kids do — to you or to one another — one day down the road.